New York City’s Tidal Wetlands: A Photogenic Journey

This stretch of rocky shoreline will soon be covered in steel and concrete—a port facility for the manufacture of wind turbines.

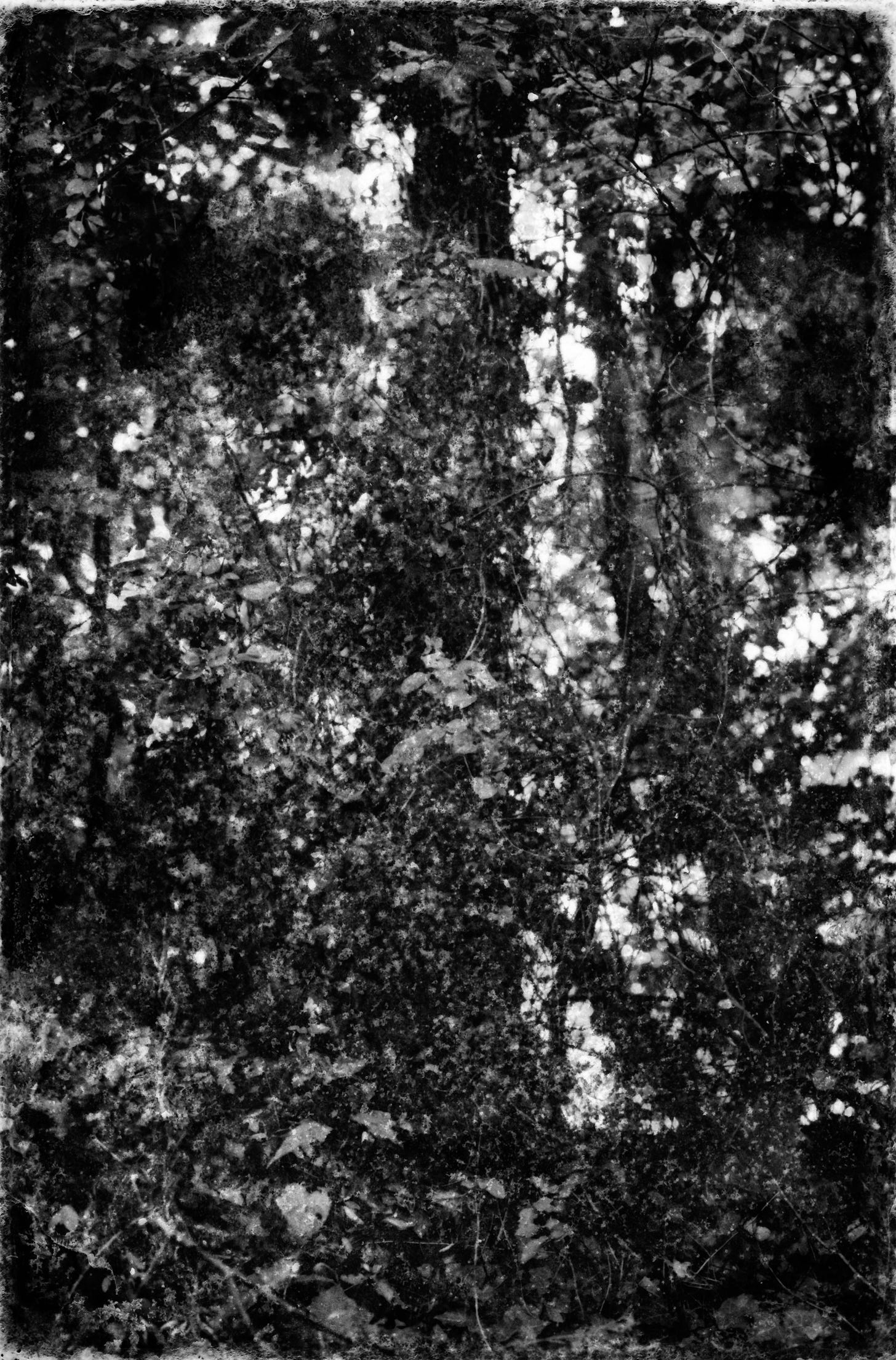

▼ These photographs were taken in a wooded salt marsh on Staten Island. At the mouth of Mill Creek where it flows into the Arthur Kill, a tidal strait formed from the eons long wandering of the Hudson River, its course straying across miles over successive ages of ice and thaw. Here are some of New York City’s last surviving tidal wetlands. The remnants of a once-vast watershed, in various states of ruin and remediation, wending its way through the estuarine periphery of Greater New York.

▼ This stretch of rocky shoreline will soon be gone. All of its teeming life — the Beavers and Eels, the Herons, Cordgrass, Glassworts and Milkweed, the River Birch and Swamp Oak, the burrows and nests — all of it covered in steel and concrete. The site of the planned Arthur Kill Terminal, it will house a port facility for the manufacture of wind turbines.

▼ A little ways down the Kill, towards the rusted ships’ hulls of the marine scrapyard, lies some of the most dangerous mud on earth. And in fact, “it is this mud,” Cal Flynn observes, in her book Islands of Abandonment, “or rather the poisons held within it, that is the true legacy of this region’s industrial past… the oil refineries, tanneries, smelters, paint manufacturers, chemical and pharmaceutical works, and paper mills that proliferated in the area during the 19th and twentieth centuries.” This legacy is crystallized in the compounds which saturate the mud, the “mountains” of DDT, the silty strata of PCBs and Dioxins.

▼ “Benthic Fauna, those bottom feeders that make their homes in the mud and the muck, are most exposed to the poison buried in the sediments: tolerant polychaete worms and soft clams and tunicate sea grapes. And among them on the seabed scamper thousands of blue-clawed crabs.” A staple of subsistence diets on these shores for millennia, “a single Newark blue-clawed crab now carries enough Dioxin in its body to give a person cancer.” The accumulated suffering and death wrought by the wanton profusion of these substances is unfathomable.

▼ And yet, if you venture out into the intertidal zone of the Arthur Kill, you will encounter a different kind of monstrosity. The Atlantic Killifish, also called the Mummichog, or mud minnow, a diminutive inhabitant of these brackish waters that, in “a few short decades” have evolved mutations rendering them “up to eight thousand times more resistant to industrial pollutants.” They are now being studied as an important indicator species; their genomes subject to recombinant divination, scoured for signs and portents, for some foresight of our collective future of living with inescapable toxicity.

▼ My way of reckoning with all this is by making photographs, or to use an earlier term for them, photogenic drawings. After all, photographic technologies, with their own legacy of extraction and wreckage, are built around natural phototrophic processes that have been bound up in the making, and unmaking, of climates for eons.

▼ From their earliest appearance in the fossil record, the light eaters are agents of climatic change. We encounter them as Stromatolites: once living Cyanobacteria, their ancient bodies entombed in mineral formations. Their sudden profusion in the Precambrian era, powered by tiny light gathering antennae, caused a catastrophic feedback loop of Oxygen emissions that irrevocably changed the composition of earth’s atmosphere. The Great Oxygenation Event, or The Oxygen Holocaust, as it is sometimes known, is thought to have killed 80-99% of life on earth.

▼ Dorian Sagan has termed this epoch The Cyanocene, pointedly framing this age of apocalypse as a mirror of our own. Writing in What Is Life?, co-authored with his mother, the evolutionary biologist Lynn Margulis, that “there is no life without waste, exudate, pollution. In the prodigality of its spreading, life inevitably threatens itself with . . . fatal messes that prompt further evolution.” The degree of comfort one takes from this sentiment depends, I suppose, on one’s faith in our capacity to effect radical, revolutionary (or re-evolutionary) change on a global scale.

▼ Reassuring or not, Sagan’s imagining of the Cyanocene at least offers up a precedent, a symmetry with which to orient ourselves on the horizon of unthinkable planetary crisis. This symmetry also grounds our past, present, and future struggles in a circular eschatology of recurrent world-endings. A kind of cosmic-ecological restatement of Nietzsche’s doctrine of the Eternal Return, in which “only that which is different returns.” This is an old idea, and a familiar one for many traditions and peoples for whom time is not linear, nor the world singular, but rather cyclical and radically pluralistic.

▼ This folding of time and space — something that photographs do, incidentally — recalls the theorist Timothy Morton’s affinity for the Möbius strip, a figure embedded in his refrain that to reckon with climate change we must first acknowledge that the end of the world has already occurred. That the derangement of climate systems has exhumed the buried infrastructure — rendered intelligible in its deformation — that previously grounded and sustained us. We can no longer feign ignorance. We must accept both the terrible freedom and the responsibility. There is no going back. Or, to put all this more succinctly, in the words of the composer and poet Le Sony'r Ra, better known as Sun Ra, “It’s after the end of the world, don’t you know that yet?”

Samuel Partal is a New York City based photographer from California. His work has been exhibited in New York, Los Angeles, San Francisco, and London.

More by Sam on TEOTWR Erosion::Antecessor: Trace fossils and last rites

▼ ▼ ▼

This is a fantastic piece--crazy to think about reindustralization as a response to deindustralization.