This Week in Books: The Basement, Where the House’s Blood Is Pumping

“The only tortures in this parallel world are the ones humans brought to it.”

Dear Reader,

Sophie Pinkham begins her review of Pablo Servigne and Raphaël Stevens’s How Everything Can Collapse: A Manual for Our Times with this quote from the book: “Utopia has suddenly changed camp. Today, the utopian is whoever believes that everything can just keep going as before.” It’s a shivery sentiment. A dark inversion.

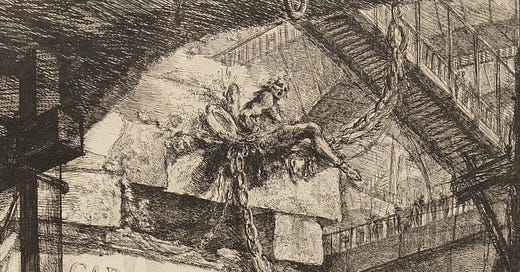

Detail from “Le Carceri d'Invenzione, plate I: Title Plate.” Giovanni Battista Piranesi, 1761.

In his essay on the life of the poet, diplomat, and environmentalist Homero Aridjis, who recently turned 80, Carlos Fonseco quotes Aridjis’s reflections on his lifelong dedication to the environmental movement. Aridjis summons up another bit of inversion, less dark but still a cool thrill: “Although the plant and animal species we defend, or the rivers and forests, will never know we defended them, often at risk to our lives, ‘in dreams begin responsibility,’ as William Butler Yeats wrote, and for me there is nothing more tyrannical than a dream.”

And in his review of Daisy Dunn’s biography of Pliny the Younger, In the Shadow of Vesuvius: A Life of Pliny, Thomas Jones points to Pliny’s self-deprecating (or not? possibly just honest?) recollection that the “accession [of a new emperor] struck Pliny as a good time for ‘pursuing the guilty, vindicating the injured, and advancing my own reputation’” — a bleak little inversion echoed by Joaquim Maria Machado de Assis in his classic novel The Posthumous Memoirs of Brás Cubas (and quoted by Lorna Scott Fox in her review of two new translations) when the posthumous narrator grimly admits that the point of all his late-in-life charity work was to “give me a really excellent opinion of myself.”

So, where have we ended up here… If I add up all these little turns… The pessimists and the utopians, these days, are united in their belief that nothing will change. The dream of liberation is itself a great tyranny. To champion the helpless and oppressed is surely vanity.

It’s a lot to take in; it’s likewise a bunch of things I knew already. The typical complaints. Conservatives have always been the most delusional of all utopians; great champions of the people have always been flawed egoists (*cough* RBG *cough*); the revolution has always been a burden. I think my mind locks in on these little flourishes, these structured orations, because they are beautiful and I am, basically, an idiot, and the rhetoric is doing its work on me without me being able to see through it, beneath it, to gaze down into the slinky, slippery basement of things and see where it all comes from, where it all goes…

Although I’ve noticed… it could be, it seems to be, that in my little newsletter this week there are attempts being made to get down there — down to the basement, where the House’s blood is pumping...

Kim-Anh Schreiber’s Fantasy is one such valiant endeavor. It is a fictionalized, memoiristic, critically theorized leap into Nobuhiko Obayashi’s phantasmagoric 1977 horror film House, or Hausu. “By putting these notes together, cutting, editing, collaging, organizing, and reorganizing, I began to understand the story of what happened,” writes Schreiber. The narrator, in the frightening spirit of the film, holds her own mother prisoner in a dream House where caricatured and primordial versions of mothers and daughters run amuck. “This time, I held her captive as a monster in a mirror, where I visited her on my terms. I conjured whole scenes and stories of the two of us together, a movie in my mind.” Writes reviewer Alex Lanz:

Fantasy reminds the reader that as we look at the often broken and crooked stories of ourselves, we can’t forget that history keeps circumscribing us, even as its content eludes us. In Fantasy, history’s effects are known through the book’s forms, its strategies for structuring itself — which doesn’t make history less hurtful…

And a sublime effort to explore the House has been undertaken by Susanna Clarke, the fantasy novelist, sure, if you want to call her that, who disappeared from the public eye for a very long time, suffering from chronic fatigue syndrome, and has reemerged unexpectedly with a second novel called Piranesi, about a character named Piranesi living inside a grand dream House reminiscent of the malarial hallucinations engraved by the artist Piranesi in 1742, called the Carceri d’Invenzione (imaginary prisons). Reviews of the book are awe-inspired and flummoxed. Reviewers want to explain it but know they can’t quite. It seems so obvious that the book should be a metaphor for… something. It almost is. It sometimes is. Little inversions abound. The friend is really a jailer. The paradise is really a jail. The jail is really a paradise. The jailer is really a friend. Reviewer Ethan Davison makes this incisive observation:

In Piranesi, the hero is happy in his prison world… When he contemplates the skeletons of former prisoners, he isn’t afraid but comforted by the idea that one day he’ll be numbered among them.

But in the final accounting, it’s impossible to make any particular metaphor add up. The structure is the structure, the House is the House, the meaning is the meaning. Concludes Davison: “The only tortures in this parallel world are the ones humans brought to it… We bring to [the House] what we take with us…”

Stay safe,

Dana

1. “The Health Insurance Plot Is the New American Happy Ending” by Nitya Rayapati, Electric Literature

Ahh! This is so clever and so terrible at the same time! Nitya Rayapati identifies a new archetype in recent American fiction like Raven Leilani’s Luster, Kiley Reid’s Such a Fun Age, and Lily King’s Writers & Lovers.

The Health Insurance Plot is a cousin to the Marriage Plot, which refers to a story that concludes in a marriage. The Marriage Plot is still prevalent today, but in 19th-century England it was especially popular. All of Jane Austen’s novels, for example, end with weddings. At the time, marriage was essentially permanent and offered Austenian heroines domestic and financial security—a kind of happy ending.

Today this happy ending is instead achieved by acquiring a job, one with great health benefits…

2. “A Beginner’s Guide to End Times” by Sophie Pinkham, Bookforum

Sophie Pinkham reviews Pablo Servigne and Raphaël Stevens’s How Everything Can Collapse: A Manual for Our Times.

…Servigne and Stevens argue that the specter of apocalypse, like the economic gospel of perpetual growth, is only a distraction from the true danger: civilizational collapse resulting from wanton exploitation of natural resources. At the end of the world we can relax, because there will be nothing left to do. Collapse, by contrast, requires hard work, because it is as much a beginning as an end. In the view of these self-styled “collapsologists,” the disintegration of national and global institutions will demand invention, resourcefulness, and a return to small, mostly self-sufficient communities that depend on local networks of mutual aid. The newly minted discipline of collapsology aims to help people prepare for this new way of being.

3. “On Randall Kenan, 1963–2020” by Marco Roth, n+1

Marco Roth writes about Randall Kenan, who passed away August 28 and whose story collection If I Had Two Wings was longlisted for the National Book Award last week.

I’d always assumed that Randall had many more books in him, so the twenty-eight-year break between his story collections Let the Dead Bury the Dead (1992) and If I Had Two Wings, released this summer, caught me by surprise. In the interim he’d returned to his regional roots, a full professorship at UNC, had conducted and edited an oral history of southern Black life at the turn of the millennium and written again on Baldwin—but the gap still startles, and should shame us. Even if it’s the case, as Elias suggested to me, that Randall might have ultimately preferred his life down home, might never have really taken to the vanities of New York. Still there are writers who should not be allowed to vanish and go silent for so long, much as they might prefer to do so. Letting them subside in this way without a fight is a cultural crime.

4. “Abroad: the distance between Calcutta and California” by Alif Shahed, Popula

Alif Shahed writes about the life of Dhan Gopal Mukerji, the Indian-American scholar and revolutionary who won the Newberry Medal in 1928 for his children’s novel Gay-Neck: The Story of a Pigeon.

The details of his life are hazy, but we know that Mukerji’s exposure to the ideals of Marxism and the Bengal Renaissance during his time at the University of Calcutta followed him to California, where he found friends among likeminded anarchists and revolutionaries. According to his memoir, Caste and Outcast, he was immediately sympathetic to the struggles of the working class and African Americans in the US. His efforts to connect the plight of oppressed classes worldwide is evident in his friendships. With W.E.B. Du Bois he wrote an editorial, ‘What is Civilization?’; he also befriended the noted Bengali Marxist M.N. Roy, who founded the Mexican Communist Party in 1917…

Today… though his reputation among academics is high as ever—has practically disappeared from the popular imagination…

5. “Memoirs from Beyond the Grave” by Lorna Scott Fox, The Baffler

Lorna Scott Fox reviews two new translations of Joaquim Maria Machado de Assis’s classic (and unclassifiable) The Posthumous Memoirs of Brás Cubas: one by Margaret Jull Costa and Robin Patterson and another by Flora Thomson-DeVeaux. Years ago I read William Grossman’s 1952 translation, lauded by Sontag and inexplicably but enticingly titled Epitaph of a Small Winner, and it shook me, as we say these days. First published in Brazil in 1881, it’s a book so ahead of its time — or altogether out of time? — that there’s a sort of freaky power to it. But an old-timey freaky power, like a “Nikola Tesla building a big antenna to harvest electricity from the sky” kind of power.

The two consciousnesses carrying the novel’s narrative in alternate or enmeshed voices—Dead Brás from his bored beyond and Living Brás in successive flashbacks—are underlaid by a third, the author’s, which can be sensed like a dissonant hum. We hear him, for instance, pointing us to the sophistry of the arguments whereby Living Brás convinces himself of the virtue of some selfish or cruel action: operations taken at face value by Dead Brás, however hard he sometimes is on his inadequate self in its successive “editions.” At one point, reflecting on cheating a muleteer who has just saved his life, he reaches the view that the sin was not meanness but profligacy, for which he is “filled with remorse.” A more honest account of his charity work late in life admits that its main reward was to “give me a really excellent opinion of myself.”

6. “‘Piranesi’ Is a Portal Fantasy for People Who Know There’s No Way Out” by Ethan Davison, Electric Literature

&

7. “‘Piranesi’ Will Wreck You” by Lila Shapiro, New York Magazine

Ethan Davison and Lila Shapiro review Piranesi, the long-awaited second novel from Susanna Clarke, author of the incomparable Jonathan Strange and Mr. Norrell. Shapiro recounts the book’s already mythic publication history:

Jonathan Strange was longlisted for the Man Booker Prize, becoming the first and only work to receive both a recognition from that prestigious institution and a Hugo Award, science fiction’s highest honor. But just a few years after the book came out, Clarke withdrew from public life. In a smattering of conversations with journalists between 2005 and 2007, she mentioned that her work on the sequel was being delayed by an illness: She had been diagnosed with chronic-fatigue syndrome, and, as the years went by and her seclusion deepened, readers despaired that she would never publish another word. At one of the author’s last public events, a conversation with Gaiman in 2007, her editor, Alexandra Pringle, noted how pale and otherworldly Clarke looked. Eventually, even Clarke’s communications with Pringle slowed. “I remember thinking at the time it was as though she’d been captured into the land of Faerie,” Pringle told me, “as if she had been taken away from us.” And then, about a year ago, a dazzling manuscript unexpectedly arrived in Pringle’s in-box. “It was the most extraordinary thing,” she said. “There was the book — complete.”

And Davison takes a shot at explaining what it all might mean:

In another, less interesting book, the drowned halls and crumbling statues of the House might suggest a ruined monument to long-dead humanity, the result of climate cataclysm. But Clarke’s Piranesi is protean. We bring to it what we take with us, and it offers no glib self-explanation. From the world of one dark brain to another, we can recognize genius; but its aims and reasons are ultimately inscrutable, as hidden to us as the conjurer’s tricks.

8. “Sheets of Fire and Leaping Flames” by Thomas Jones, The London Review of Books

Thomas Jones reviews Daisy Dunn’s In the Shadow of Vesuvius: A Life of Pliny, a biography of the Younger, as opposed to the Elder, Pliny — although it does include the Younger’s disturbing account of how his uncle the Elder died during an astonishingly lackadaisical rescue attempt of Pompeiians during the eruption of Vesuvius. Here’s another bit of color:

Domitian was assassinated in September 96. His successor was 65 years old and childless. Nerva had served under Nero, helping to expose the Pisonian conspiracy, and been consul under both Vespasian and Domitian. His accession struck Pliny as a good time for ‘pursuing the guilty, vindicating the injured, and advancing my own reputation’. He made a speech in the Senate attacking Publicius Certus, who during Domitian’s rule had denounced one of his friends. As Pliny got up to speak, a colleague ‘rebuked me for coming forward so rashly and recklessly ... I had made myself a marked man in the eyes of future emperors. “Never mind,” I said, “as long as they are bad ones.”’ (‘Esto, inquam, dum malis.’)

9. “A Poet of Mythologies: Homero Aridjis at 80” by Carlos Fonseca, The Los Angeles Review of Books

Carlos Fonseca writes about the life of the poet Homero Aridjis, who recently turned 80 under lockdown. Collections of his poetry available in English include Eyes to See Otherwise and Solar Poems. As Fonseca explains, Aridjis is also an ardent human rights activist and environmentalist:

Aridjis has always been outspoken, fearless, and independent. In 1997, shortly after being elected president of PEN International and during a time when journalists were being murdered throughout Latin America, he received death threats. He and his family lived with government bodyguards for a year. As a pioneer of environmental awareness, he has been resolute and courageous in advocating for measures that might check our ongoing climate emergency. The International Environmental Leadership Award, bestowed by Mikhail Gorbachev and Global Green USA, is one of many environmental honors he has received, and during his three years as Mexico’s ambassador to UNESCO, he endeavored to convince the organization to endorse environmental education at all levels.

Indeed, Aridjis has become one of the great contemporary spokesmen for an abused and silenced nature. As he elegantly states in his extraordinary News of the Earth, a translated collection of his environmental writings published in 2017:

“I have often felt like Sisyphus, confronting the same environmental problems over and over again, or Cassandra, prophesying disaster, or Don Quijote, because we sometimes seem like madmen tilting at windmills. Although the plant and animal species we defend, or the rivers and forests, will never know we defended them, often at risk to our lives, ‘in dreams begin responsibility,’ as William Butler Yeats wrote, and for me there is nothing more tyrannical than a dream.”

10. “Fantasy – Kim-Anh Schreiber” by Alex Lanz, Full Stop

Ah, here it is, a book I didn’t even know I’ve been waiting for! As Helen DeWitt’s The Last Samurai is to Kurosawa’s Seven Samurai, as Theresa Hak Kyung Cha’s Dictee is to Dreyer’s The Passion of Joan of Arc, so Kim-Anh Schreiber’s Fantasy is to Nobuhiko Obayashi’s 1977 masterpiece of weird horror House. Yes, you heard me correctly, this book is a personal and intellectual journey into the bleeding heart of House. Reviewer Alex Lanz gives a sense of the book’s vibe:

The last section of the book is a play called “The Maternal Ecology.” There are still long descriptive passages, and the daughter continues her narration, now as a character in a house that serves as a new setting. Schrieber tells us earlier in the book that Ba’s house is the house of her dreams, and Omi’s house is the house in her heart. Walter Benjamin wrote of the dream house, filled with passageways and furnished with our many desideratums, but with no outside. The setting is a dream house in that sense, onto which the daughter projects scenes with her mother. “This time, I held her captive as a monster in a mirror, where I visited her on my terms. I conjured whole scenes and stories of the two of us together, a movie in my mind.” This is an up-to-date dreamhouse with cameras and innumerable monitors, playing clips of House and other female-centered media from the 70s. It’s also literally broken, falling apart. There is Mother and Daughter and also Grandmother V and Grandmother Z, as well as — another doubling — a mother flower and daughter flower named Karma and Khaos, with sister flowers, living alongside the other characters.

11. “Landscapes of Memory” by Saleem Haddad, The Baffler

Saleem Haddad reviews two new novels by Palestinian authors: Adania Shibli’s Minor Detail and Ibtisam Azem’s The Book of Disappearance.

Both writers were born in 1974 and can be considered a part of the “post-Oslo” generation… If Palestinian literature of earlier generations was largely driven by nostalgia for an idyllic pre-1948 past, these novels are an investigation into what remains: the ghosts that linger in the ongoing, slow-burning, ethnic cleansing of a land.

12. “Shola Von Reinhold’s ‘Lote’” by Izabella Scott, The White Review

Izabella Scott reviews Shola von Reinhold’s novel Lote.

The novel opens in the National Portrait Gallery archive in London, circa 2019. Mathilda has been recruited, without pay, to sift through a donation of photographs… Mathilda comes across an image unlike one she’s ever seen before: a costume party held at Lady Ottoline Morrell’s Garsington Manor, where her beloved Tennant appears beside two women bedecked as Renaissance angels. One flaunts a pair of feathered wings and a fine chain mail suit, grasping a champagne coupe – and her skin is black. Her afro doubles as a kind of halo, ‘brushed into a commanding nimbus’, enthuses a mesmerised Mathilda. ‘It made me ache with jealousy and bliss.’ Entranced, she steals the photograph, determined to learn more about this Black pleasure-seeker – and thus the book slips into gear. Who is this Black Bright Young Thing, and why is she absent from the history books? As Mathilda will discover, she is a Black Anon who exists only in fragments – appearing in scraps of gossip (often defamatory), and cited in sources that can’t be tracked down…

13. “Gold Buggers” by Nathan Ward, The Los Angeles Review of Books

Nathan Ward reviews Paul Starobin’s A Most Wicked Conspiracy: The Last Great Swindle of the Gilded Age.

The mastermind of the scheme was Dakota political boss Alexander McKenzie, of whom The Seattle Times hyperbolized only slightly that “McKenzie is in North Dakota what Napoleon I was in France.” More specifically, Starobin explains, McKenzie was:

“a maker of US senators, with connections to the Executive Mansion, as the White House was then called, and to the most powerful business moguls in the nation. […] Naturally, he planned to cut in his friends. This was, after all, the time in American life known as the Gilded Age, and the bosses operated like lords of the realm, dispensing and receiving favors as a matter of course. The question was, Who would stop him?”

14. “Karen Solie, ‘The Caiplie Caves’” by Michael Autrey, Chicago Review

Michael Autrey surveys the work of Karen Solie and reviews her latest collection of poetry, The Caiplie Caves, inspired by the life of the hermit-saint Ethernan, who is said to have dwelt in the Caiplie Caves in Scotland. Writes Autrey:

Ethernan’s retreat to the Caves looks like an attempt to get away from it all, including the poor with whom he is identified and the so-called religious authorities. “A visitation” begins: “Paul, why are you here? / I would sooner send my spirit out walking between the hailstones // than have you drive it to its corner on the fork of your advice[.]”

Detail from “Le Carceri d'Invenzione, plate XV: The Pier with a Lamp.” Giovanni Battista Piranesi, 1761.

▼ ▼ ▼