Find Something To Hide As Soon As Possible; an interview with Anne Boyer

“What I want to say about our vulnerability, then, is that it should instruct us. We need to get ready.”

These days it can feel like we have resigned ourselves to being reduced to data points. COVID-19 and its consequences are discussed through the language of test and trace, lagging indicators, positivity rates, unemployment numbers, shut-downs, and that disgusting phrase “social distancing.” Of course these things matter, but as with all technocratic vocabulary, the mess of ourselves, the human, has become lost in a tangle of warped meaning. Who better to remind us what has been lost, what is at stake, and what can be regained than a poet?

“Miscellany — Mr. Bramah's patent lock ; Mr. Rowntree's patent lock / … del. ; Lowry scul.” Wilson Lowry, engraver, 1814.

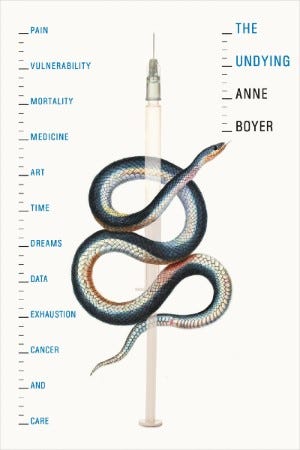

I reached out to Anne Boyer because her book The Undying, a memoir of her experience with cancer, is about the rebellion of reclaiming the self behind the data points. This feeling carries over to all her work, especially her recent essays about COVID-19. Boyer hopes — against hope, as they say — for a better future, but her optimism does not come easy; her optimism is not even particularly optimistic. According to Boyer, this all sucks and it’s going to take a lot of work to make things even slightly tolerable.

Over email we discussed Boyer’s initial reaction to the pandemic, how things have been going since then, and why it feels like no one is able to respond adequately. Along the way we also discussed advice and dreams.

Anne Boyer’s book The Undying, winner of the 2020 Pulitzer Prize for General Nonfiction, is out in paperback.

▼

Sam Jaffe Goldstein:

At the beginning of the pandemic you wrote a very hopeful short essay that states, “We face such a strange task, here, to come together in spirit and keep a distance in body at the same time. We can do it. I am writing this because I want the good in us to break through the layers of hateful nonsense we've been drowning in.” At the same time Michel Houellebecq wrote a radio essay about how everything was going to stay the same but get worse. I toggle between the two sides, but I wonder five months later how you feel about your reaction versus his.

Anne Boyer:

When people say “everything is going to stay the same, but get worse” it seems more likely they mean “everything will feel the same, but worse,” which brings about the question, to whom? Literary men have a tradition of declaring that feeling of unchanging banality to be a fact, all the way back to Solomon at least. Houellebecq, Solomon, et al, are actually engaged in some performative ironic juxtaposition with the undeniable condition of incarnated mutability. When they moan “It’s the same, just worse, such vanity” we get the signal to take up our part and disprove the poet’s lie, to challenge critically what we might have only absorbed ambiently. These guys do us a favor by compelling us to utter “no” to their parroting of the ruling class lie that things can’t or at least won’t change except for the worse. Ahistorical sameness is necessary to the status quo because to admit that all this bullshit of the ruinous social order is fleeting is fatal to their interests. We are to believe their domination is as natural and unchanging as the sun in the sky, which itself is a lot more changeable than we once thought.

The pandemic doesn’t really alter this — not incarnation’s law, poet’s irony, ruling class deceptions — but it does provide clear evidence of what’s up. What we were told would go on forever has been proven, in 2020, fragile and illusory. Things have totally changed, will change, are changing. The “get worse” part of the formula is worth some consideration, though not worthy of certainty. Again, the question — for whom?

We are vulnerable to the virus right now and I am wondering how we should think about that vulnerability?

This is the “get worse” part. The ultra-rich are behaving like the ultra-rich, plundering the future, grabbing up the trillions in “quantitative easing” that the Fed printed, devouring real estate with an eye on future rents, using bail out money for stock buybacks, and amassing nearly inconceivable gains since March. The pandemic seems to have accelerated an economic restructuring, too, in which the service economy is transforming, at least in the US. Servers become delivery drivers. Retail workers become warehouse workers. The Post Office might be stripped, further isolating already abandoned and impoverished rural areas, and its work now done by poorly paid contractors without unions. The workers who get these jobs will be, in context, the “lucky” ones, as the economic contraction will reduce employment. Higher ed and arts organizations, too, seem headed toward a cliff. Those of us who once made art will now, more than ever, be pushed into making “content” which is delivered only over social media platforms owned by the same ultra-rich who steal the days from our calendar and the minutes from our hours. The economic inequalities of gender and race could deepen, now painfully accompanied by showy superficial concessions to equity among the upper classes — more diversity among the elite few tasked to crush the many. The perpetual crisis itself is having a crisis. All this, and a virus, too. What I want to say about our vulnerability, then, is that it should instruct us. We need to get ready for this all out intensification of class war. The streets this summer have become training grounds for the push back. This is the season of whetstones, not tweetstorms.

How has it been in Kansas City? I know that Kansas allows counties to decide whether or not mandate masks. Have you witnessed this "debate" play out in your day-to-day life?

How it has been in Kansas City is the murder rates are rising. The poor are getting poorer. The wealthy are safely in their homes, zoom-ing and doordash-ing and prime-ing. Suffering is often distributed by race, as it has been throughout the city’s history. The vulnerable get sick and die, hidden away in the territories radiating off from the city — the prisons, nursing homes, meat packing plants of the hinterlands. The gardens look better than ever, and even the wealthy now have social justice signs in their yards. The police and national guard responded, at first, to the protests here with cavalier violence, raining tear gas on kneeling people, pepper spraying children. Young people are facing federal charges for spray painting “racist” on statues of racists. The “progressive” city government keeps both-sidesing everything, which they sort of did with the pandemic, too, and at first they were denialists, minimizing the virus, casting aspersions on masks, then later condemning the people who continued to do what they did at the beginning, as if they weren't saying the same “flu” nonsense on day 1. As far as I can tell, people have caught on here now and wear masks, behave somewhat carefully, but I have generally only been out to Aldi or the protests so I am no expert on compliance.

I’ve been spending some of my time in rural Kansas, too, and there it is a different story. Unless it is a national chain like Dollar General, which has a top down mandate, no one wears a mask. It occurred to me that maybe the non-compliance means that life is so grim lately for so many people that they are unattached to the outcome of their actions, have no faith that they have any say in living or dying. I’m just guessing, but it could be the case that any bluster about freedom might be a front for despair.

We are inundated with information about coronavirus and have spent months arguing over what data we can and cannot trust. Is our obsession with data getting in the way of telling the story of this pandemic?

Something is wrong, but I don't know if it’s our obsession with data. The thing-ification and fragmentation the data does to us is perhaps growing into a visible contradiction, in that trusting the numbers is no longer a widely shared value, but I do not know where this leads. What has me really despondent is the lack of collective public mourning, the absence of memorial, ritual, recognition, rage. If anything, in this case, the data should help us conceptualize the magnitude of our loss. Maybe data has become so cheap now that we cannot feel the preciousness of what it represents. The covid dead don’t seem to, in the public imagination, come near the death of Princess Di, Prince, or whatever celebrity. We could fill up acres with fresh graves, and yet there is no shared time or place in which we all come together to mourn.

There is also a paradox because we both rely on data to understand our world but a worthy political goal is to reclaim ourselves from those who control the data about us. Is this possible?

We ought to at least assume it is possible until we’ve tried and failed. The reclamation of data, or whatever it will be — the “restoration” of life and death against data’s undead partiality — might actually come about in unexpected ways. Maybe we are already heading toward this transformation. A starting point might be the critique of the very form of meta-data and its reign over so much of life, including our self-perception. Another start might be understanding “data” in its physicality, denying it its aura of eternity. We should know where the data centers are located, what they look like, who owns them, where and how they get power, how and by whom they were made, who maintains them, who guards them, how they might someday decay or be destroyed.

Have you been dreaming recently? What have some of your dreams been?

I dreamed I had a pet rattlesnake who rode shotgun with me through the streets of the suburbs. I insisted he wasn’t venomous, until my loved ones finally convinced me that he was, and I had to leave him in the parking lot of Sally’s Beauty Supply. He was a talking snake, as many dream snakes are, and starred in another dream in which both the snake and the mouse he was about to eat gave me speeches — one in defense of eating, the other in defense of not being treated as food. I’ve also been dreaming of pogroms, civil wars, firing lines, assassinations — all lurid, devastating, bloody. It makes me grateful I am not employed as an ancient oracle or there’d be a lot of trembling people leaving the temple. I also dreamed a friend was cursed to perpetual creative writing job interviews, like he was strapped to a boulder and creative writing was an eagle eating his liver.

There is a semi-viral clip going around of a landlord in the Kansas City area kicking out a tenant. This story is about to play out in millions of homes across the country, but I was wondering if there was anything you wanted to communicate to the literati about the situation on the ground right now?

Nothing is as effective at instantiating collective resistance than people being put out of their home by jerks like him, spouting nonsense next to a shiny red truck. There will be, I think, a fierce display of unity around housing rights in the coming year, and I hope this extends to writers, too. Poets, especially, have always been the special enemies of landlords. I wouldn't be surprised if the next few years bring us the first novel written in a landlord’s tears. Tenant struggles have an advantage over workplace ones during economic crises. When a claim to dignity is bound only to work, it leaves a great number of people (children, unpaid caregivers, the elderly, the disabled) out, but when our claims center on housing — a universal need — the struggle expands. It also gives the fight a location — the home to protect — and a moral simplicity. Shelter — and dignity — should not depend on whether you have a job or how much it pays. Society should, and must, be organized around need, which I say every year, but this year I am happy to say I feel like a small voice in a growing chorus. I’m optimistic about this part of the fight.

Speaking of the literati, why do they seem so disconnected from what's happening on the ground right now? Is it just that they have money and are safe? There does seem to be a current failure of the literati to describe, understand, and work through this moment. Is that an unfair characterization because no one was prepared or do you think there is something uniquely wrong with those in the arts & letters?

I sometimes struggle to find evidence in contemporary literature and the conversations around it of one of the most basic material facts of our era: in order to live, the vast majority of people have to sell the hours of their lives at work. Or some others: nearly everything around us is owned, and almost everything owned was built (by people and out of something), or that all of this is threatening to fully deplete our common home, the earth. How strange that we live in the epoch of hour selling, in a made world in which we do not acknowledge the makers, in an arrangement of space in which trespass threatens every step, in a world in which no extractable goes unextracted, and yet much of the most lauded literature locks this up like a secret inside itself. The structure of reality becomes, in our books, a hidden chamber unlocked only with the question, “but who made this world?” The books themselves hardly ever seem to ask it.

For example, I am not sure that beyond the work of radical poets, I’ve ever seen much mention in literature that a car requires gas, that the gas requires the oil industry, the oil industry requires imperialist war, etc. Instead, people in books move via invisible fuel in machines that are visible only as reflections of character, like a Ford Fiesta is not a material fact but a mere symbol of selfhood, running on biographical oil. I sometimes imagine some alien reader picking up a contemporary novel and thinking that everything about our species in our time and place was feelings, self-identification, self-interest, self-fulfillment, self-determination, that humans were made from the inside out, instead of the outside in, and that the only relation to objects we had was our curation of them.

So of course, if this was the condition of things before covid, it shouldn’t be surprising that the pandemic at first seemed to spawn a subpandemic of solipsism. I had to stop looking for a while at what writers were writing because I wanted them to be better, then that Harper’s letter came out with all those dignified signatories demanding superficial and abstract freedoms and omitting to even mention the concrete and pervasive unfreedoms that undergird all. Which is not to say I like what everyone is up to on Twitter, either. You can have a voice, social media promises, but don’t go around thinking we are going to give you anything else.

Those of us who spent time there were often wasting away our lives and talents filling out the forms of billionaires, manipulated by the algorithms into trying to ruin each other in ways we would never do if we were in our right minds, face to face with any sensate mammal, even a problematic one. But I would have hoped Noam Chomsky, at least, if not the rest of them, could have understood that the problem we face is not a problem of not having enough free speech, and it is not of individuals making poor, correctable choices on the internet, but rather having a life in which freedom takes the perverse unfree form of the “free” market, our feelings corralled into profitable data, our hours eaten up by anxiety and work.

At the beginning of Adam Curtis’s documentary Hypernormalization (which isn’t great) there’s a scene that uses Patti Smith walking around downtown Manhattan to explain that the left now just experiences collapse but does nothing to stop it. How do writers avoid, if it is even possible, the pure act of just rearranging our sensibilities to notice the beautiful light hitting the sinking titanic.

When the revolutionary poet Roque Dalton was imprisoned awaiting execution, an earthquake brought down the wall of his prison cell. His response was not to simply experience the collapse, nor was it to try to stop it. Dalton's response to the collapse of his prison was to recognize the opening and make a door from what once had once been the prison wall. Some things that collapse are rightly respecting the force of gravity.

So much of your work is about surveillance of our bodies and minds. What advice do you have for those who say they have nothing to hide?

If you have nothing to hide, I recommend finding something to hide as soon as possible. Acquire as many secrets for yourself as you can. Be like sphinxes and 19th century anarchists. Don't forget the glamor of the words enigma and clandestine! You might even want to take up my recent hobby, which is hiding things from myself via forgetting.

What about for those who are worried about the eyes in the sky?

I am going to quote Victor Serge here, from his journals — something he said to a friend:

“I added that I have a boundless love for contemplating the starry sky, that for me it’s both a need and a pleasure, and that I never look at it without expecting a cosmic event or catastrophe, as if a star were suddenly going to expand and explode — as if an enormous star were going to arise and fill the night with fire — my feeling that this would be natural, that the serenity, the calm of the sky and the immobility of the constellations aren’t natural, or in any case not definitive.”

There is a line in the acknowledgement section of Garments Against Women about the “possibility of a literature that is not against us.” What would a literature that is for us look like?

I don’t know. When a person is thrown away like a piece of trash and a piece of trash (i.e. property, as all property is future trash) protected with the deadly force a parent might use to protect a child, subject has been object and object has become subject, and that is a fucked up arrangement of the world. Things become like people and appear to take on a life — even rights — of their own.

On the flip side, people are made to be as things in that they are fractured, injured, used up, wasted, exploited, branded, self-exploited, self-branded, tossed out. Or we are made to be something even more wretched than things, in that we live as things — as instruments of work, domination, competition, etc — but unlike things, we can be overwhelmed with feeling. We are made as things with melancholy, things with imagination, things with rage. But we are not things. The whole process depends on a soulless world in order to become totalizing, complete. There is no such thing as a soulless world. Whatever you forgot to sell, whatever couldn’t be consumed or debased, whatever hides away, whatever can never be ground up into sellable particles of metadata, whatever exists in the relation of love against the relation of profit, whatever refuses a brand: this is the soul, the organ of refusal.

The way things are now cannot be total, no matter how fervent any insistence that this is all we get. Can a fucked up world make a non-fucked up literature? Probably not. Can we give up trying? No. Why not? Because of the very capacity of a “no,” of the soul itself, which humans possess together, contains within it the ingredient of the possible, including a possible literature and a possible world.

My friend (in their late twenties) was recently diagnosed with colon cancer. Are there any words that you think I should share with them?

What I’d tell you is that you should never forget your friend is themself and very specific, even if cancer and treatment begins to work its anonymizing force. But this is probably just good advice for everybody about everybody no matter what the crisis. This is also why I’m terrible at wise-words-for-cancery-times, because every person is a person, each with different needs and priorities, and what comforted me could be awful for someone else. I could say to watch the film Daisies on repeat, but it might not do the trick. The only meaningful word I can share with you to share with them is the one made for times like these: “solidarity.”

I emailed Anne Boyer to ask her for book recommendations after receiving some inquires on Twitter about what kinds of books she likes. I put the reading list she gave me on Bookshop, so you can see it there. -Ed.

Sam Jaffe Goldstein is a bookseller in Brooklyn. You can find him on twitter at @sgiraffe666.

▼ ▼ ▼